Article by Prof. Aant Elzinga, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

A major role of scholarship in the Humanities has always been to reflect upon civilization changes – some of them drastic – and to provide society with the means to cope with or adapt to these changes, while drawing from and appraising the knowledge of the past. The following are some recent external events or trends presently changing the role of the Humanities:

– globalization: it has led to greater internationalism, and it is evoking countervailing trends in which national and ethnic identities (often with potential ‘balkanisation’ tendencies) sometimes confronts cohabitation-style multi-cultural diversity. Globalization also introduces new mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion, noticeable also in the uneven development of resources for research and asymmetric patterns of collaboration and interconnectivity in the global landscape of so-called knowledge production;

– geopolitical re-arrangements of boundaries in the world and subsequent human reactions;

– environmental problems and global approaches to these;

– unprecedented media development, entailing excessive commercialization, short-sighted fixations, oversimplification of world events;

– advances in communication technologies (e.g., ‘cyberspace’ and communication highways), with their downsides of informational overload and emerging ethical and political issues relating to personal integrity and freedom of speech, etc.;

– advances in medical technologies with ethical implications, and likewise with nanotechnology where ethical, legal and social aspects (ELSA) are also increasingly recognized;

– the spreading of literacy/illiteracy and the need to promote widespread scientific literacy as a prerequisite for public understanding and governance of science, which has become an important policy issue for education at various levels, including the university.

A central thesis that emerged in the course of an evaluation of 11 humanities disciplines across all universities in Switzerland already some ten years ago (commissioned by the Swiss Federal Research Council in Bern)[1] was that the humanities are in the process of modernization. The Swiss higher educational and research system in the realm of the humanities was particularly old fashioned, whence the trends identified manifested itself in striking fashion in comparison. On the part of the natural sciences, conceptually and ideologically this modernization manifested itself earlier in discourses over “two cultures”, a notion introduced by the British writer C.P. Snow during the 1950s when he contrasted what he found to be progressive features of the natural sciences with backward ones in the humanities.

As Stefan Collini writes in his Foreword to a recent edition of C.P. Snow’s book The Two Cultures, the great division between the natural sciences and the humanities is not a product of the Enlightenment. Rather, it emerged first towards the end of the eighteenth century and becomes explicit during the mid-nineteenth century, about the same time as the words “science” and “scientist” appear. “…the Enlightenment’s great intellectual momentum, L’ Encyclopédie, did not represent human knowledge as structured around a division corresponding between the ‘sciences’ and ‘humanities’”.[2] Today, Collini argues, the problem is not so much the division between two cultures, but with increasing specialization over the past thirty years and more we have a multiplicity of disciplinary cultures and creative diversity of views – hence one might as well speak of two hundred and two cultures, or on the other hand fundamentally one culture. In the present epistemic landscape what used to be called humanities therefore face a challenge that goes far beyond the role of the individual disciplines; the challenge of communication and representation.

In the face of commercialization and consumerism, and with these trends towards the dominance of an instrumentalist rationale for knowledge production, it has become even more important to go back to and give new content to some of the traditional values associated with scholarship in the humanities. Or as Collini puts it, “…the utilitarian public language of modern liberal democracies, which is intensely suspicious of non-demonstrable judgements of quality and intolerant of non-quantifiable assertions of values, makes it easier to justify fundamental research in the natural sciences, with its promise of medical, industrial and similar applications, than to justify what is anyway with some awkwardness called ‘research’ in the humanities”. To this one might add that the “audit gaze” promoted promoted when methods of New Public Management move into one societal realm after the other is now also pushing the universities to what Daniel Greenberg calls campus capitalism. New regimes of perceptibility and (ac)countability fix only on what can be measured in would-be-quantities, i.e., spurious numbers, and the metrics determine who and what is “seen” and therefore “counts”. In this respect the specialist’s disdain for communicating to a wider audience may, as we move along to the end of this first decade in the twenty-first century, have – again in Collini’s words – more practically damaging consequences for the well-being of the humanities than of the sciences. By extension, this is also damaging for society at large.

On the other hand, many humanistic disciplines such as archeology, history, art history and theology enjoy a general public audience, which most other disciplines (perhaps with the exception of psychology) are lacking. This shows a broadly felt need for information about cultural phenomena – especially those contributing directly to a society’s sense of community – and the capability of specialists to express themselves about their research in a generally understandable narrative. The undervaluation of this social function of the humanities by many utilitarian-minded authorities is at odds with the sales figures of books and the demand for cultural tourism, which reflect these public needs.

In the light of the foregoing, a rationale for the humanities as seen in the prism of the modern (and post-modern) Kulturwissenschaften (as distinct from the older term Geisteswissenschaften) may be summarized in a few points:

– self-reflexive, critical sciences which are profoundly hermeneutical, i.e., related to interpretation and assignment of meaning to human life;

– concerned with values and criteria for choices affecting agency, action and behavior;

– profoundly enriching in contributing to personal growth (Bildung), the education of the “human spirit”, the celebration of life and the enhancement of persons and communities:

– Centrally dealing with communication systems (words, artifacts, and signs).

According to the authors of the much-debated book by Michael Gibbons et al., The New Production of Knowledge (1994), what we are seeing is a change in the mode of scientific knowledge production. The centre of gravity of research in some cases appears to be moving out of the universities and to institutions outside, where the distance between producer and consumer of new ideas and practices, is smaller or non-existent. This tends to play into the reconfiguration of knowledge production, its primary structures, career and reputational systems, as well as prestige. In the natural sciences strategic brokers try to promote research environments that are at one moment competitive and at another collaborative, and this process is spilling over into the domain of scholarship. Networking has now been a buzz-word for some time, in the belief that the ability to mobilize and control resources count for more than actual capacity to produce knowledge at its site of “ownership” in the traditional sense. This is having an effect on the social conditions of academic research and its epistemological thrust. Epistemic landscapes are changing, with more emphasis being placed on transdisciplinarity, at least by “users”, if not by academic scholars themselves.

Disciplinary and faculty boundaries are not only the result of a division of labor in a learned mapping of various dimensions of reality. They are also a consequence of complex histories of vested interests, financing, entrepreneurial opportunities and academic coalitions and leading personalities. In other words there is an element of culture and cultural shaping in the social and cognitive dynamics of academic disciplines when these are viewed over time.[3]

The humanities have for a long time been left out of consideration in OECD research policy documents and the like. However now they are being recognized as having a utilitarian potential, even if it is mostly left to the European Science Foundation and the newly created European Science Council to try to stimulate multi-national projects and research programs in our fields. The authors of The New Production of Knowledge devote a whole chapter to the place and future of the humanities, noting among others that interaction with the natural science, engineering and medicine will increase. To be sure, during times of budgetary expansion, public accountability tended to be forgotten, and it became natural for academic scholars to perceive their positions as a kind of entitlement. In times of contraction (simultaneously as numbers of scholars increase), as relevance and accountability pressures are brought into the foreground, one may find a variety of responses from the side of academe. What we have found in the course of diagnostic evaluations of the Swiss landscape of humanistic scholarship is three ideal-typical responses. On the one hand there are those who argue that the humanities are part of a country’s cultural heritage and pride, on which no other utilitarian measures should be placed than that they are for the good of our soul. Humanities should be promoted on their own premises, without having to be legitimated in terms of societal usefulness. This may be called the traditionalist approach. Ultimately here a variety of fields of scholarship, like Byzantine studies, Sanskrit and others whose fortunes have declined during the past fifty years, would be defended as disciplinary species that should be protected from extinction. In other words one might argue in such cases for a policy of conservation of threatened species, along lines similar to what one finds in the realm of Nature preservation – epistemic diversity as an analogue to bio-diversity. Another, more utilitarian line of thought here is to see the humanities as having compensatory potential. In a society full of stress and dehumanization under pressure of modern machine culture, the humanities are thence held to provide a breathing space, a vehicle to escape to other values. When developed into a more instrumentalist direction this “theory of compensation” (as it has been called in the German-speaking academic world) provides a basis for promoting the humanities as a palliative.

A second approach to the humanities is the overtly pragmatic one. Here one emphasizes the instrumental utility of research in the humanities, history for the tourist industry, language to meet the challenge of a Europe in transition, computer linguistics for machine translation and contributions to cognitive science, ethnology for its importance in understanding cultural identity creation processes, etc. The basic assumption is that the humanities need to be revitalized in order to play a more prominent role in social, economic and cultural life. Interaction and competition with natural sciences, engineering and medicine is no stranger to this approach.

A third point of view we found in debates about the humanities is that of “critical theory”. Emphasis in this case is on the social responsibility of scholarship with regard to its significance for society’s critical self-understanding, and to people’s emancipation from every form of suppression, both of body and mind. In this respect scholarship in the humanities is valued not only for its retrospective interpretations of past historical events, but also in how such narratives may provide guidelines for a democratic future, encompassing ourselves and “the other”. Critical thinking is given a special place. Exponents of the approach may be found in the wake of research inspired by Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism, as well as amongst feminist scholars in various fields.

Of course the three approaches referred to here do not stand out as separate and distinct doctrines or policy justifications. In practice, within university institutions and even in ourselves as scholars all three of these motivational strands may be found to a greater or lesser degree. At the institutional level the mix is more complex.

Going back to the distinction between Geisteswissenchaften and Kulturwissenshaften in the discourse in the German-speaking academic world, it may be interesting to note how the conceptual framework associated with the former categorization of humanities was shaped by epistemological boundaries laid down in the nineteenth century by German philologists, and in the quest of scholars that sought to distinguish themselves from the natural sciences by invoking a distinctive method of their own, hermeneutics.[4] If so, does this imply an elitist ideal of scholarship, which was once defined by and belonged to a socially and culturally privileged group? And, to what extent, seen in retrospect, did it carry the signs of an anti-technocratic escape hatch out of Modernity? By contrast the later concept of Kulturwissenschaft does not automatically equate modern industrial society with “mass society” and the dominance of the technical world, a theme intensely debated in the 1920s during the Weimar Republic. Instead it seeks to understand the process of modernization in all its dimensions. In this perspective, modern mass societies are seen as both products and producers of culture. At the present time, this concept is central to a critical discourse of reflexive modernity, which in turn has become the subject of some controversy.

As some critics have argued, also, the definition of Orientalism as it emerged qua discipline within the Geisteswissenschaften, for example, because it was constituted in the nineteenth century in tandem with a self-conscious nationalism, assumed (more or less tacitly) an idea of Western progress and evolution, tied to imperialist supremacy expressed by more overt means. Today, new forms of nationalism and large power hegemonism (including in the EU) once again can draw on earlier cultural goods for sustenance. It was in such a past context too that anthropology had its origins in certain countries, practically and epistemologically. One finds, when looking back, a coincidence of social and epistemic orders. Some writers in the field of science and technology studies have introduced the co-production thesis when referring to similar resonances between science and society at ideational (conceptual and metaphorical representations) and practical instrumental levels.

One may well ask, is there historically speaking an inertia or cultural lag, and if so to what extent do Geisteswissenshcaften as a category with a past history of managing epistemic boundaries between different disciplines within the humanities and between them and the natural sciences, implicitly or perhaps even subliminally, still influence current conceptualizations? Do they still have a similar function, and if so does this have a bearing on their epistemic kernel and limit their interpretative flexibility even today, referentially or hermeneutically? The concept of Geisteswissenschaft presupposes an opposition between science as a life of ideas and material sciences, a dichotomy which belongs to the past. On the other side, as we could see in the course of our evaluations, the concept – and the denomination – of cultural sciences/Kulturwissenschaften takes into account the recent developments of technology in society and of the very broad interdisciplinarity demanded for humanism in the 21st century. The older idealistic concept diminishes the social responsibility of critical knowledge, which today is fundamental to democratic societies. The semantic field and meaning of the concept Geisteswissenschaft has thus significantly shifted since the nineteenth century, and the disciplines to which it refers have also considerably changed and been transformed.

The cultural sciences can and have to develop an interpretation, not only of the patrimony accumulated during the past, but also of the actual and often conflicting tendencies, which are leading to the future.

We don’t want to overemphasize the concept of “material culture”, which in any case in some instances should be replaced by the concept of “material evidence of culture”.

It appears to be very important also to reject a dichotomy based on the human sciences on one side, and the natural sciences, engineering or technical sciences and medicine on the other.

Developments in the natural sciences, engineering and medicine during the past three decades have rendered C.P. Snow’s notion of Two Cultures obsolete, at least in practice; even though we are sorely aware how the division remains in the mentalities and still tends to trigger heated and endless discussion whenever it is mentioned in contexts dominated by mainstream scientific practitioners and scholars.

The challenge posed by anthropogenically caused climate change, the calls for sustainable ecological development, but also sustainable cities and urban landscapes, artificial intelligence, patenting of genetically engineered forms of life, the screening for genetic diseases (even before one is born), and the advent of new industrial materials such as composites, new ceramics, or adhesives based on advances in surface chemistry and physics, reconfigurations of functional materials coming out of nanotechnological laboratories, all these are prompting critical events that (should) bring the two communities, the natural sciences and the humanities, closer together.

We see it reflected in new trends in philosophy, religious studies, history and social studies of science, ethnology, feminist studies on ethics of reproductive technologies. Ethics of research is something that concerns not only the natural sciences, but equally the humanities and social sciences. Other areas of partial convergence are through methodological rapprochement in archeobotany with paleoclimatology, or in archeometry, and in the interface between cultural studies, cognitive science, and art. Art history and architecture ought to interact more intensely in future. New materials are having an impact on architectural design and music that must be taken into consideration by some of the aesthetic disciplines. New computer aided visualization techniques, data-mining, and simulation modeling, are having an impact that cuts across many domains, both natural scientific ones and humaniora. In recent research on the brain the effects of drugs are being monitored by careful targeting and proxy visualisation on computer screens, as scientists search for the neurochemical basis of human emotions and experiencing or self-identity. What remains of the authenticity of self-reflection when psychiatry offers us pharmaceutical means to change not only our feelings but even our whole personality at will, as one does with changes of clothing style and body-cosmetics to suit the occasion?[5]

The reductionism immanent in modern brain research as well as molecular biology falls back on a biological materialism that, philosophically, has long historical roots back into the history of ideas and culture in the West.[6] Indeed the very concept of what it is to be human is impacted by such developments, increasing the need for self-reflexivity of the kind traditionally associated with the humanities. Understanding the social history of technologies is one particular aspect that is worth mentioning in this context, especially since it is an area largely absent as an academic discipline in some countries. Like the history of science, this discipline can play an important bridging role in the gap so often construed between the so-called “two cultures”. In the same spirit a possible opposition between cultural sciences and social behavioral sciences seems to us problematical, because culture is based on social life and is therefore not unfamiliar to sociological methods of enquiry.

When asking for a rationale for the humanities it is also necessary to ask in what context such the question is being posed.[7] Does it come from academe, from governmental agencies and research planners, or from those concerned with business and industry or the accumulation of economic wealth in society? A forth possibility is that the question reflects the concerns of people involved in social movements or in short, civil society. Thus we may conceive of the co-existence of multiple, competing forms of rationality, sustained by different forms of social cohesion and ideology, whence analysis of policymaking may locate the interaction between science and politics in four main “policy cultures”: academic, bureaucratic, economic and civic. These coexist in industrial countries, competing for influence and resources, and seek to steer science and technology, as well as scholarship in a broader sense, in different directions. Each policy culture has its own doctrinal assumptions, its images and ideals of science, and its own political constituencies. In this model, a policy framework is the outcome of the mutual conflict and accommodation among contending policy cultures, some of which are strong and others weak (i.e., the civic policy culture). Thus the civic culture’s interest in democratizing the governance of science and learning by allowing more diverse inputs or by making it more socially amenable and accountable resists and seeks to overcome the bureaucratic culture’s insistence on making policy more rational, scientific or rule-bound, or the academic culture’s predilection for unchallenged autonomy and self-regulation at the behest of professional academic oligarchies.[8]

In the coming together of four “policy cultures”, several relationships between scholarship in the humanities on the one hand and society on the other may be at issue. Let us distinguish at least three such relationships along the lines suggested above (p. 2) in terms of three different responses to external relevance and accountability pressures:

a) a symbolic ornamental relationship;

b) an instrumental relationship, and,

c) a democratic relationship.

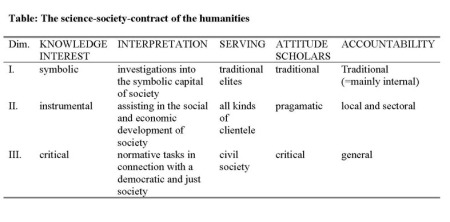

Different aspects of the three dimensions of the “science-society-contract” concerning the humanities may, furthermore, be distinguished. In each dimension a different interpretation of the humanities is at stake (see Table).

When the symbolic interest is prominent, the humanities can be seen as studying and inquiring into the symbolic capital of society. In case the instrumental talk of humanities is underlined, their symbolic function is supposed to be useful for the economic and social development of society. And when the critical or emancipatory interest comes to the fore, a normative task can come in view as well: the humanities can now contribute to the establishment of a more democratic and just society.

It may be clear that in the three cases the humanities are serving different kinds of groups. In the first case mainly traditional elites come into view. In the second case it is a question of new kinds of clients, from the world(s) of government, business, medicine or mass media, whereas in the third case civil society (“all citizens”…) in general may become relevant.

In the three dimensions we are also faced with different (though in some respects overlapping) attitudes of the scholars concerned, related to the different kinds of accountability.

In the first dimension their attitude may be mainly traditional and their accountability likewise: existing disciplines are protected and the way things used to be done is directing the way future tasks are fulfilled.

In the second dimension this may not be enough. New tasks that are advocated from the part of society may open up new research topics and even stimulate the formation of new fields of scholarship. Here, the attitude of the scholars concerned may (ideal-typically) be more pragmatic than exclusively traditional and their accountability may be local and sectored. The new clients are supposed to have a say in the establishment of research priorities and benefit from its eventual outcome. “Participation” and “governance” have become favorite buzzwords in this context.

However the humanities should not become completely dependent on the interests of existing agencies. There are also general interests which they are supposed to respond to (concerning various kinds of “commons” that go beyond particular interests, i.e., beyond particularism), like they have done sometimes in the past, fulfilling tasks, which now, in hindsight may be described as traditional. A post-traditionalist society with a lot of conflicting social and economic interests is in need of means and instruments to discuss and direct its general course and to compare democratic legitimations with social reality itself. Here the humanities have a critical task to fulfill and their accountability is general instead of local. By taking care of these general democratic interest (countering both particularism and reductionist tendencies) are not becoming dependent, as is sometimes thought. On the contrary, precisely in this way, their scholarship can preserve a certain intellectual autonomy by studying and discussing things nobody asks or pays for and by putting forward questions that those in power don’t always regard as opportune.[9]

The three dimensions referred to above are also taken up in critical theory (Adorno, Horkheimer, Habermas, etc.), which however tends to depict them as mutually exclusive and totalizing. For our part, as is already evident from the foregoing presentational scheme, the three dimensions highlighted to not have to be mutually exclusive, rather they can be seen to combine and interplay.

Of course, one can serve the interest of traditional elites in such a way that there is no space for more pragmatic or even critical activities. However, if one travels in our scheme from the other direction and starts at the bottom, the relation between the three dimensions changes drastically. It does not make sense to forget your traditional stock of knowledge when you are required to accept new tasks and the same goes when it comes to responding to the democratic responsibility of scholars (not only qua intellectuals) in our fields.

In other words a readiness to be accountable in a general way, and to accept that there are some problems of democracy and of justice in one’s society, can help to assess and to evaluate also more traditional and pragmatic task, for example by contextualizing and introducing some mode of reflexivity. Ideally the three dimensions we have referred to – the symbolic, the instrumental and the democratic or emancipatory – can become, at least partly, integrated, notwithstanding the fact that the establishment and acknowledgement of a new dimension.

Göteborg, February 2009

[1] The evaluation involved a panel of 24 academic experts from various European countries, led and coordinated by Aant Elzinga. The present paper builds in part on the introduction to our final report.

[2] Stefan Collini, in C.P. Snow, The Two Cultures (Cambride University Press, Canto Edition Cambridge 1993), p. x.

[3] For a philsophical perspective on the emergence, structuration and function of different university faculties in Europe, at about the same time as Vannevar Bush in the U.S.A. was writing his bleuprint for national science policies implemented in the post-war era, see Karl Jaspers, Die Idee der Universität (Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1946) which is an update of his booklet with the same name from 1923 (reprinted by Springer-Verlag, Berlin/New/York 1980).

[4] Of course hermeneutics has also undergone a series of shifts of meaning since its inception in the nineteenth century, from Schleiermacher to Dilthey, and the subjective turn to Heidegger, followed in our own day by the controversy between Gadamer (accenting tradition) and Habermas (emphasising critique) and the extension to a hermeneutics of ’suspicion’ by Paul Ricoeur. For a review of the idealist heritage of the concept of Geisteswissenschaften in an historical perspective see W. Frühwald, H.R. Jauss, R. Kosseleck, J. Mittelstrass, and B. Steinwachs, Geisteswissenshaften heute. Eine Denkschrift (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M., 1991), esp. pp. 22-44; here the notions of Kompensationstheorie, Ackeptanzwissenchaften and other issues (like the mythological character of C.P. Snow’s ”two cultures” thesis) in the German debate of the latter half of the 1980s is also taken up. Also see Peter Weingart et al., (Hrsg.), Die sogenannten Zukunft der Geisteswissenschaften (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M. 1991).

[5] This manipulation of feelings is also referred to as ”cosmetic psychopharmacology” – see Peter D. Kramer, Listening to Prozac (Viking Penguin Books, New York 1994).

[6] For a critique of reductionism in brain research see Steven Rose’s book, Lifelines. Life Beyond the Gene (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003), Ch. 10,, ”The Poverty of Reductionism”.

[7] The French philosopher Michel Serres reminds us that a new ”social” contract in the case of knowledge production is insufficient. For the natural sciences, he argues, it is urgent to introduce a contract between humankind and Nature, a contract predicated on bioethical and ecological principles that does not privilege ”man”. Cf. Michel Serres, Le contrat naturel (Ed. F. Bourin, Paris 1990). This implies a different image of nature and therefore also of science, bringing once again the natural sciences and humanities or cultural sciences closer together.

[8] Cf. Aant Elzinga and Andrew Jamison, ”Changing policy agendas in sc ience and technology”, in Sheila Jasanoff et al. (eds.), Handbook of Science and Technology Studies (Sage, London 1994), esp. pp. 527-529.

[9] For a discussion of democracy and the critical role of the scholar qua intellectual see some of the essays in the anthology by Lolle Nauta et al., De rol van de intellectueel (Van Gennep, Amsterdam 1992). Nauta was a philosopher of science in the Netherlands (now deceased) who held the chair of philosophy at the University of Groningen from where he inspired a new generation of critical scholars in the history, philsoophy and social studies of science.